Wednesday

17 June 1970

06:59

My Father experiences overwhelming relief and soul-crushing disappointment, in quick succession

“So, while undeniably regrettable in certain respects, I genuinely believe it will prove to be in everyone’s best interests.”

Calmly and rationally, yet kindly, My Father is explaining to My Mother why, after very nearly 20 years of marriage, he has decided he must put their union asunder. They are in the airy high-ceilinged kitchen of their home in Worplesdon. The conversation is going surprisingly well.

My Mother requires clarification. “Everyone’s?”

“Well, yours as well as mine, I mean. I honestly believe you’ll be happier without me.”

“What leads you to that conclusion?”

“The obvious fact that our needs and wishes have become increasingly incompatible. In particular, I have a strong desire to live in London, while you are happier here in Worplesdon.”

“But that has long been the case. I see no reason why we shouldn’t continue to lead largely separate lives, while remaining married.”

My Father unveils his most compelling argument. “But that, I feel strongly, would be unfair on you.”

“Unfair on me? How so?”

“In my view, it would clearly be unreasonable of me to expect you to ‘keep the home fires burning’ (for some reason this phrase feels resonant to My Father) indefinitely, while I range freely in the great world, unconstrained by domestic obligations.”

My Mother seems persuaded by this. She looks sad, but resigned. “Well, if our marriage is indeed over – which I profoundly regret – there are at least two things that console me.”

“I think I know what the first is.” My Father prides himself on his empathy with women’s feelings.

“As you suspect,” says My Mother, “it’s that we do not have children. Just imagine how difficult they would find it if their parents were to go their separate ways; how painful and disruptive it would be in their young lives.”

My Father nods his fervent agreement. “And your second consolation?”

“That no third party is involved. To lose you because of a fundamental incompatibility in our preferred modes of living is galling, but for you to be lured away by another woman would be intolerable.”

“As you say, if that were the case, though fortunately it isn’t, you would be fully entitled to feel….”

My Father is interrupted by the phone – of modern design, purple, mounted on the wall alongside the kitchen corkboard – starting to ring.

He knows it could be Aitken, who has his home number. Or possibly Beloff. And yet, instead of answering it, he lightly flexes his knees – once, twice, three times – and effortlessly propels himself through the open French doors into the garden…. where his momentum continues to carry him upward, until he is looking down, like a hovering bird of prey, not just on his own garden but on those of his neighbours…. and then higher still, into the downy white clouds, which look so invitingly soft and cool and pillowy that he wants to lay his frazzled head upon them…. so very like a pillow….

As My Father slowly surfaces, the sun already seeping under the curtains of his hotel room, his mind and body, and his entire being, are gorgeously suffused with relief. He’s done it! And, after all the agonising and prevarication, it really wasn’t so bad, after all. In fact, it could hardly have gone better.

And then, less than an instant later, his sense of wellbeing is swept away by a mighty crashing incoming tide of despair. He hasn’t done it! It still has to be done! And, in the waking world, where he definitely does have children, and where there certainly is a third party, what he still has to do remains a nightmarishly difficult proposition; impossibly difficult he would say, if he didn’t know that all his future happiness, everything he desires and aspires to in the remaining years he has upon this planet, depends upon his detaching himself from My Mother, publicly, definitively, and very soon indeed.

The phone is still ringing. Groaning, My Father rolls heavily onto his side, to reach for the receiver, on the bedside table.

“Good morning! This is Sandra on reception, with your 7am wake-up call.”

“Thanks,” grunts My Father.

“Cheer up, love,” says Sandra, detecting the misery in this monosyllable. “It’s another stunner of a Manchester morning.”

For some reason, Sandra’s cheerfulness and the warmth of her Mancunian vowels bring into My Father’s mind the thought that something of value may, in fact, have been imparted by his dream. Perhaps he can leave My Mother without making any incriminating reference to the Woman He Loves?

After all, My Mother has doggedly remained oblivious, over many years now, to all My Father’s wanderings from the marital straight-and-narrow. Never once, when he has returned home with lipstick, metaphorically or sometimes literally, daubed about his clothing and person, has she chosen to challenge him. Never once has she directly questioned whether all his abrupt disappearances to make urgent phone calls to journalists were what they purported to be. Never once has she seemed to doubt the existence of Ian, the kind colleague upon whose uncomfortable sofa My Father has so often been forced to sleep, after working late.

Of course, she’ll have to know about the Woman He Loves one day. Well, fairly soon; the Woman He Loves is insistent that their relationship must become “real”, as a matter of urgency. But perhaps not quite yet, thinks My Father. Perhaps the transition from suburban paterfamilias and salaryman to metropolitan lover and homme politique can be managed in stages, to lessen the inevitable pain and disruption for all concerned? He really thinks he might be able to get away with it, at least for the first few months.

“Thanks, Sandra,” says My Father, a little of the relief seeping back into his system. “Thanks very much indeed.”

***

07:25

My Father is reluctantly impressed by the PM’s ability to multi-task

In his suite, to which My Father is admitted by Marcia, looking surprisingly tiny in her stockinged-feet, the PM is seated at a small table eating the first of a pair of soft-boiled eggs, while making notes on a typescript document, and talking – via a phone clamped between his shoulder and ear – to the Home Secretary, who will be handling this morning’s final press briefing of the campaign, back at Transport House.

He seems in ebullient mood.

“It’s all-out attack, Jim. No holds barred. Not a backward step. Do I make myself clear?”

As he listens to the Home Secretary’s response, the PM somehow manages, by means of an endearingly sweet boyish smile and some quite complex improvised sign language, to greet My Father and convey to him that he should help himself to any of the unappetisingly congealed breakfast items laid out on the coffee table.

“Good,” he says, into the phone. “Let’s hear what you’ve got. I have My Father with me, so speak up.”

The PM, who is holding the phone in a more conventional manner now, cocks his wrist, so that the mouthpiece is pointing roughly in My Father’s direction.

“Well, I think it all comes down to this sentence, PM,” says the Home Secretary, clearly but tinnily. “To doubt the value of your own currency, as the Leader of the Opposition did yesterday, is just about the most heinous thing you can do.”

“Heinous?” repeats the PM, making eye-contact with My Father.

“Maybe ‘despicable’?” suggests My Father. “Otherwise excellent, Home Secretary.”

The conversation meanders on, with no further pressing need for My Father’s input. He pours himself a cup of coffee – lukewarm, oddly meaty-tasting, so utterly dissimilar from the heady throat-scouring brew that goes by the same name in the home of the Woman He Loves. He turns his attention to the papers, which are spread out on an otherwise unoccupied sofa.

Again, they are not as bad as he has feared.

Naturally, the Tories’ devaluation scare is on every front page, except the ever-loyal Mirror‘s. But the righteous anger of the PM’s defence, particularly the accusation of economic treason, has obviously gained some traction, and the coverage is surprisingly even-handed. (“The Tories launched their final pre-polling day offensive, raising the grim spectre of devaluation….”; “Labour responded furiously, with a strong personal attack on Mr Heath….”)

Overall, coverage of the latest opinion polls predominates – and this My Father finds much more worrying. No one is predicting a Tory victory; the speculation all relates to the scale of their defeat. One poll gives Labour a lead of nearly 9%, which would leave the PM wielding a majority of around 150 on Friday morning. Yet at the other end of the spectrum – the totally terrifying, blood-freezing, panic-attack-inducing end – another poll puts the Labour lead at just 2%, bringing a Tory victory well within the margin of error.

The PM has finished his call now, and gets up to pour himself more tea. (His plebeian choice of morning beverage has long since been noted by My Father, with mild contempt, and added to the bulging file of evidence against him.) Looking over My Father’s shoulder, he comments approvingly on the only other story to make the front pages.

“Good old Enoch! Still fighting the good fight, on our behalf, right up until polling day!”

The fight in question is non-metaphorical. A rally in Mr Powell’s Wolverhampton constituency, which started in celebratory mood in honour of his 58th birthday, is reported to have ended in a mass brawl, after hecklers chanting “Sieg Heil!” were ejected from the hall by stewards, and set up upon by some of the West Midlands’ brawnier guardians of racial purity.

My Father arranges his face into a wry smile, and grunts affirmatively. Can the PM really be so obtuse as to believe that the current upsurge of extreme anti-immigrant sentiment, orchestrated from within the Tory party by Mr Powell, is clearly and unequivocally to Labour’s electoral advantage? It’s almost 20 years since My Father last went door-to-door canvassing (in Birmingham, coincidentally, not so far from Wolverhampton), but he will never forget how easily – even then, in the earliest days of mass immigration from the Commonwealth – the staunchest life-long Labour voters could be seduced by any kind of xenophobic rhetoric. Right now, My Father feels certain, good old Enoch is the Tories’ most potent last minute vote-winner, regardless of the disunity within the party that he embodies.

Marcia has her heels on now, and the energy in the room abruptly changes, as she calls the campaign team to order, announcing that the cars will be outside in 20 minutes.

Rather in the manner of a squadron leader briefing war-weary bomber crews, she reminds them of the day’s key objectives. The programme she outlines consists of a lightning-fast tour of three more marginals, followed by the last major event of the campaign, a lunchtime meeting at the Metro Vickers factory in Trafford Park; then, in the afternoon, a visit to Kaufman’s (rock-solid Labour) Ardwick constituency, before heading to the PM’s traditional general election base at the Adelphi Hotel in Liverpool, and a final evening meeting at the Empire Theatre. The schedule, she impresses upon them, is very tight indeed, and only achievable if all members of the campaigning team conduct the day’s business with iron discipline, and refrain entirely from “effing around” or “blathering on” or any other form of time-wasting activity.

Still adding the finishing touches to the speech he will deliver at the lunchtime meeting, the PM does not give the impression of a man fully focused on what he is hearing.

“Happy, PM?” Marcia asks, pointedly, as she finishes.

Not looking up, the PM only waves a distracted hand in assent.

“I said, ‘happy PM?”’ This quite sharply.

The PM lays down his fountain pen, penitently, and gives her his full attention. “Blissfully, Marcia,” he says, and seems to hesitate before deciding to go on. “Except I can’t help feeling that we could be using the final day of the campaign to more positive effect.”

My Father groans inwardly. He knows what the PM is referring to. In the latter stages of the campaign, he has repeatedly urged that, instead of focusing their efforts on Labour-held marginals, they should go on the offensive, targeting safe-ish Tory seats, which he believes could be winnable. Marcia knows this is what he means, too.

“PM, I thought we had settled this,” she begins, sternly. But for once, the PM interrupts her. He seems suddenly energised by the thought of taking the fight to the Tories in their gin-and-Jaguar heartlands.

“No, Marcia, we may have discussed it, but I am still unable to see the point of spending the little remaining time we have in constituencies that are more likely to be devastated by an earthquake on Thursday than to return a Conservative Member of Parliament!”

“Shoring up the base, PM” snaps Marcia. “It’s simple electoral common sense.”

“Not if the polls – even the least optimistic ones – are to be believed,” he replies. “Why shouldn’t we be a little more ambitious? We can afford to be! Why don’t we pop over to Crosby, or Wavertree, or even Southport, and see if we can stir up a Socialist uprising among the blue rinses?”

For a moment, Marcia lets this hang in the air, which crackles and thrums between them. Their eyes lock; hers incandescent, his – what, mischievous, apprehensive, cowed? My Father unconsciously compares the quality of her anger with that of the two most important women in his life, noting how she deploys silence almost as effectively as My Mother, but combines it with the imminent threat of volcanic eruption that he finds so strangely adorable in the Woman He Loves.

“Are you seriously suggesting, PM, that we should just tear up today’s itinerary, let down countless thousands of our most loyal supporters who are expecting to see you, and swan off to Southport, where there would be every possibility of your being lynched?” Marcia says this with the heroically self-restrained calm of a reformed psychopath willing himself to leave the newly sharpened meat-cleaver on the kitchen counter.

Will the PM back down? Or will he insist on following his political instincts – widely acknowledged to be among the finest ever possessed by anyone – by taking the campaign off-piste, and into enemy territory on this its final day?

Very different from the PM’s, My Father’s reading of the polls puts him firmly on Marcia’s side of the argument. If Labour are to win on Thursday, the base, he believes with terrified conviction, urgently needs not just shoring up, but reinforcing, bolstering, fortifying, buttressing, and surrounding with barbed wire and sandbags.

To My Father’s relief, the PM gives way, as he almost always does when Marcia is in this mood.

“Shoring up the base it is,” he murmurs, raising his right hand to his forehead, in something resembling a salute. And he shuffles off towards the bedroom to root out Mary (who is absorbed in composing a new poem), in preparation for what My Father suddenly realises could well turn out to be their last ever day’s campaigning.

***

08:35

My Father’s Younger Son is maliciously disbelieved by his schoolfriends

Because it is Wednesday, when Form 2 Alpha have double Music after lunch, My Father’s Younger Son is arriving at school with Van der Graaf Generator’s new album tucked under his arm. If interrogated under the influence of a powerful truth-drug, he would be forced to admit that this belongs to his elder brother, and that he himself has only listened to the opening track on side one, which he found disconcertingly bitty, discordant, and frantic-sounding, and not really to his taste at all. But for the purposes of this afternoon’s Music Appreciation session, it is currently his favourite album; something of an acquired taste, perhaps, but, once properly understood, a magnificent densely textured epic of jazz-infused “progressive” rock, which makes most other contemporary music look gauche and infantile. He hopes that Mr Husband – the weedily effete and ineffectual teacher who has introduced these bring-your-own sessions in a desperate attempt to prevent his lessons cartwheeling into anarchy – will agree to play After the Flood, the 14 minute anthem that closes the album, in its entirety. My Father’s Younger Son has been practising some faces he will make while listening, and he intends to say the “magnificent densely textured epic” thing, as the closing mellotron chords fade out.

Cautiously skirting the combatively contested fourth form football match at the upper end of the playground, he finds his three closest friends – Webber, Kirkland and Atkins – already sitting on the low wall alongside the CCF hut, where they congregate before Assembly. Kirkland, My Father’s Younger Son notices immediately, is cradling a blue plastic carrier bag containing an album, which, from the protruding top inch or so of the sleeve, he strongly suspects to be by The Groundhogs.

My Father’s Younger Son goes on the offensive. “Blues rock! Ace!” he says, ending on a curious gurning head-waggle, which is this friendship-group’s invariable code for “direct opposite”. They seem recently to have entered a phase in which withering sarcasm – verbally and/or visually expressed – is almost the only mode of communication available to them.

“Yours?” enquires Kirkland, in his precocious baritone. Unlike his milky-breathed pre-pustular friends, he is one of those 13-year-old boys who resembles an only-slightly scaled-down replica of a full-grown man.

My Father’s Younger Son rotates his album which, unaccountably, he has been holding front cover inwards.

“Van der Graaf Generator?” For an instant, Kirkland is non-plussed by the name, which means nothing to him outside the context of a recent Physics lesson. But the sleeve’s florid artwork is a give-away.

“Oh, progressive! Not tedious at all!” It’s his turn to do the gurning head-waggle now.

“At least they can really play their instruments.”

Kirkland isn’t having this. “Oh come on,” he splutters, too outraged to be sarcastic, “have you even heard McPhee’s solo on Rich Man, Poor Man? I mean really listened to it?

By way of reply, My Father’s Younger Son closes his eyes, bends his knees, and awkwardly mimes an ecstatic Guitar Hero posture, encumbered by the album he is holding. “Widdly, widdly, widdly, widdly, widdly, widdly, widdly, weeeeeee!” This is his scathing approximation of the amorphous torrent of notes that pour from the strings of the most admired exponents of blues rock guitar, such as Tony (TS) McPhee.

This catches the attention of Webber and Atkins, who have been comparing their Latin homework. Amused, they add a few widdly widdly wees of their own. Kirkland fails to see the joke. But, sensing that his advocacy of the virtuosic musicianship to be found within his preferred genre is doomed to fall on deaf ears, he abruptly changes his point of attack.

“So what’s your Dad up to today, then?”

Now it’s My Father’s Younger Son who is unamused. But all three of his friends – suddenly united against him – are enjoying themselves.

“Celebrating mass with the Pope?” says Webber.

“Training the astronauts for the next Apollo mission?” suggests Atkins.

“Touring with Simon and Garfunkel?”

“Helping the Queen choose new curtains at Buckingham Palace?”

If this has the air of a well-rehearsed comedy routine, that’s because it is. Over the last few months, and particularly during the period of the election campaign, My Father’s Younger Son’s friends have richly entertained themselves by finding satirical new ways of expressing their disbelief that My Father is a key adviser to the PM, and a regular visitor to Downing Street.

Perhaps, by now, My Father’s Younger Son’s dogged and unwavering insistence has, in fact, convinced them that this implausible-sounding story is true. But he has made the fatal mistake of allowing them to see that their incredulity wounds him. So naturally, their professed disbelief has only become more unshakeable. And their pleasure in returning to the subject has grown, day by day.

But today is different. Today, My Father’s Younger Son is going to settle the matter once and for all, and wipe those stupid mocking smiles from his so-called friends’ faces. Because today, in addition to the new Van der Graaf LP, he has brought something else to school: irrefutable documentary proof that what he says about My Father and the PM is true.

Unruffled by his friends’ continued mockery (“Practising for Wimbledon, with Rod Laver!”; Playing the villain in the next Bond film!”), he puts down the album carefully, leaning it upright against the wall, and opens his briefcase. But, at the very moment his hand reaches into it, the bell rings for Assembly, and Kirkland, Webber and Atkins break off in mid-jibe, to gather their things and head inside.

My Father’s Younger Son’s moment of vindication will have to wait until later in the school day.

***

09:25

My Father is requested to lend the PM a trifling sum – Bolton West (Labour, majority 4,917)

The final day of the campaign has begun in lacklustre fashion. Here in the Manchester area’s third most marginal Labour seat, it’s too early for a satisfactory Prime Ministerial walkabout. The crowds of factory and office workers who formed a Lowrey-esque tableau on these streets an hour or two ago have disappeared now. The few passers-by – early shoppers and harassed-looking mothers propelling pushchairs – are easily outnumbered by the PM’s party, which has been swollen by the arrival of the local MP, accompanied by his wife (by no means an electoral asset in My Father’s eyes), his agent, three or four nonentities from the Party’s regional office, and a small police contingent. To further skew the balance between professionals and public, an unimpressive knot of journalists and photographers, none of whom My Father recognises, stand around, looking bored, smoking and drinking from flasks (thermos and, in a few cases, hip).

As the campaign team departs from Point A, which is the Co-op, the supreme political campaigner of his era is reduced to accosting pedestrians hurrying by, trying to avoid eye-contact. Mary, who has a low embarrassment threshold, discreetly detaches herself from her husband, and wanders off to look in shop-windows. And when the PM does eventually succeed in engaging a member of the local electorate, the woman – advanced in years, pushing a shopping basket on wheels – turns out to be staunchly Tory.

“You know, filling that basket will take a bigger bite out of your hubby’s pay-packet, if your lot win!” twinkles the PM.

“I’d pay twice over, to be rid of you!” she snaps back.

He only laughs at this, apparently with real amusement, and murmurs “Touché” – which strikes My Father as deeply telling. He’s never seen the PM allow anyone, let alone a civilian, to have the last word before.

By the time they reach Point B (in this case, the Town Hall), the temperature is rising, and jackets are coming off – though the PM has so far obstinately refused to remove his. My Father can feel sweat trickling down between his shoulder blades. And there is something resembling a crowd awaiting them, including a fairly sedate group of Tories (it’s still too early for anything in the way of fervour) brandishing home-made placards, (Labours broken promises!, BETTER DIE THAN DEVALUE!!!).

As the PM mounts the Town Hall steps, someone hands him a microphone, which turns out to be non-functional. He briefly blows and whistles into it, before counting to 10 in Latin. The Tories, becoming aware of the technical hitch, take heart and start heckling (“It doesn’t bloody work – just like your government!”). And then the PM does something really unexpected. Instead of waiting impatiently for someone to fix the problem, or grabbing a megaphone, or simply raising his voice to make himself heard, he shrugs and passes the microphone resignedly to My Father, who is at his elbow.

“A bakery!” he remarks, looking across the road. “My wife is very partial to a jam doughnut. Oriel, do you possess sixpence?”

***

10:30

My Father is present at the birth of the photo-opportunity – Bury and Radcliffe (Labour, majority 4,471)

In the Manchester area’s sixth most marginal Labour seat, the temperature is considerably higher, in every sense. The sun is up, and the crowds have come out now. And as the PM and his party approach Point B (the local TGWU office), it’s clear his supporters are heavily outnumbered by highly vocal opponents. There is chanting (“What do we want? Labour OUT! When do we want it….”), jostling (though luckily a significant police presence has now materialised, and formed a protective phalanx), and egg-throwing (so far inaccurate).

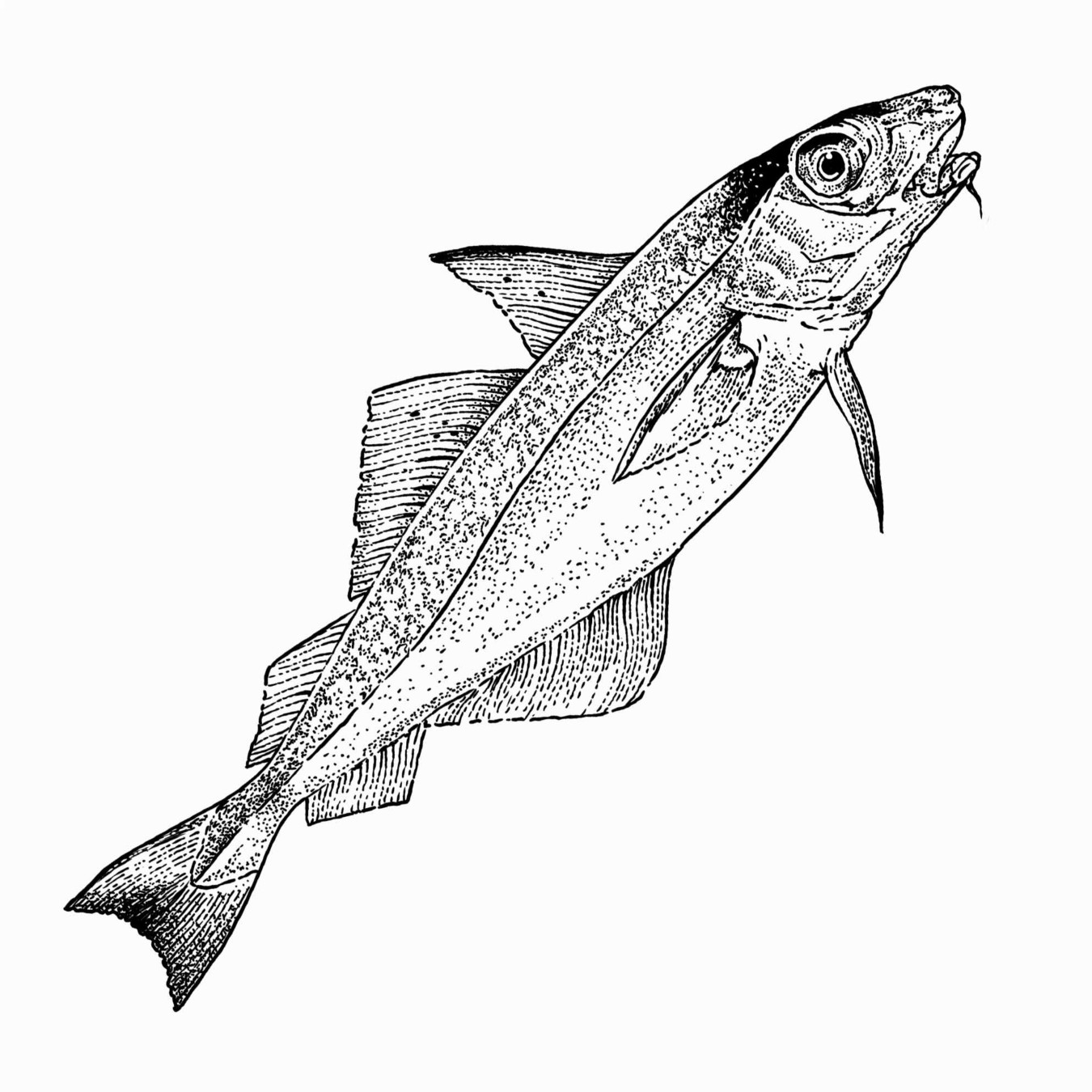

To the surprise and consternation of his team – they are, after all, on a very tight schedule – the PM grabs Mary by the hand, and ducks into a fishmonger’s. The gentlemen of the press are quickest to respond, following him inside en masse. By the time My Father manages to gain entry, the PM is behind the counter, wearing a white trilby which he has borrowed from the proprietor, and holding aloft a large fish – possibly a haddock – for the benefit of the cameras.

Above the whir and clack of their motor-drives, the PM can only just be heard making some remark about his Conservative opponents having had their chips, and perhaps also being in for a battering.

This may not, in fact, be the first time a senior politician has adopted a frankly foolish pose, while wearing some garment associated with the world of honest toil, in order to deflect attention from a point of weakness. But it’s from today that this manoeuvre becomes a mandatory component of every well conducted campaign.

***

10:45

My Father’s Younger Son is denied the vindication he craves

“Well, I for one am completely convinced,” says Webber.

“Me too,” says Atkins. “More than completely. Totally. Utterly. Unreservedly.”

“I think I speak for all of us when I say we’re sorry we doubted you,” says Kirkland, gurning and waggling.

My Father’s Younger Son’s friends still don’t believe him! He has produced his incontrovertible documentary proof, and after giving it a cursory glance, here they are…. unhesitatingly controverting it.

“What makes it so convincing,” elaborates Webber, “is that it definitely couldn’t be a fake.”

“No, quite impossible!” agrees Atkins.

It’s Kirkland’s turn to say something satirical, but he’s just taken a large bite out of a pork pie (it’s break-time, and the boys are in their form-room, finishing what they didn’t eat of their packed lunches on the way to school), so he only raises his hand, palm outwards, to indicate that he will have something to delight them, as soon as his mouth is empty.

“But you can see it isn’t fake!”

Once again, My Father’s Younger Son can’t prevent himself from saying what he really means. And to make matters worse, his voice – which won’t start to break for another six months or so – sounds wobbly and shrill, almost as if he’s on the brink of tears.

His friends all gurn and waggle, but say nothing.

“How could I possibly have faked it?”

He picks up his documentary proof, which just a couple of minutes earlier he slammed down triumphantly on the desk, like a gambler unfurling the hand that will break his opponent’s heart.

“I mean, look at it….” he falters, holding it out to them.

They do. It’s an A5 sheet of notepaper. In the top left corner, there’s an embossed coat of arms, above the legend Prime Minister; in the top right, a simple address, in quite complicated Gothic script: 10 Downing Street, Whitehall. And underneath, handwritten quite legibly, there is a message: For My Father’s Younger Son, with my very best wishes…. followed by the PM’s signature.

“How could I possibly have faked it?” he asks again, with a detectably imploring note.

Kirkland has finished his mouthful now. “With one of those printing kits kids get given,” he says matter-of-factly, doing a palm-slap-to-the-forehead gesture they use to mean “too obvious to be worth saying”.

This is clearly an absurd suggestion. It’s true the PM’s message could easily be a forgery, but the headed notepaper – stiff, imposing (despite its modest size), expensively produced – could not, realistically, be anything other than what it purports to be. My Father’s Younger Son knows this. And he knows that his friends know this. In which case, they must also know it is a thousand times more likely that his story about My Father being an adviser to the PM is true, than that a 13-year-old schoolboy from Worplesdon has somehow managed to obtain access to the Prime Ministerial stationery cupboard. Yet Kirkland, Atkins and Webber – My Father’s Younger Son’s three closest friends – are immoveable. It’s more fun not to believe him.

But not that much fun. As, with trembling hands, My Father’s Younger Son tucks his documentary proof back into his briefcase, they have already lost interest, and started chucking pellets of bread and empty fountain pen cartridges at each other.

Why does his friends’ disbelief upset My Father’s Younger Son so badly? Partly, certainly, because of its heartlessness. But more, perhaps, because it seems so unfair. For years now, My Father has been in retreat from his children’s lives. His increasingly rare visits to the family home are brief, and unsatisfactory for all concerned. (Sunday’s, for example, consisted of him arriving too late for lunch, then closeting himself in his study for a couple of hours, before emerging to conduct a short sotto voce dispute with My Mother in the kitchen, immediately followed by his abrupt departure.) Anxious and sad by nature, My Father’s Younger Son keenly, though barely consciously, regrets the absence of a reassuring paternal presence in his life. So is it unreasonable of him to expect that, by way of compensation for what he has lost, he should enjoy a little bit of reflected glory, a smidgen of prestige by association? (“He may not want to be my Dad any more, but at least he’s on first name terms with the most powerful man in the land!”) Is that really too much to ask?

It seems it is.

Kirkland comes over and puts a consoling hand on his upper arm. “Hey, My Father’s Younger Son,” he says sympathetically, though just loud enough to be heard by Atkins and Webber, “I hear Cassius Clay is looking for a new sparring partner!”

***

11:20

My Father sees further evidence that the PM is in end-of-term mood – Stretford (Labour, majority 3,365)

“WIN-STON!” – stamp-stamp-stamp – “WIN-STON!” – stamp-stamp-stamp – “WIN-STON!” – stamp-stamp-stamp – “WIN-STON!” – stamp-stamp-stamp….

Outside Point B (a Methodist chapel) in Manchester’s most marginal seat of all, a large, well organised yet rowdy group of Tory supporters is making it difficult for the PM to present his case to the local electorate. More than five years after the death of our Greatest Statesman, their raucous chant would seem inexplicable if not for the fact that the Conservative candidate here is none other than the Telegraph columnist and right-wing firebrand Winston Churchill, namesake of his rather more renowned grandfather.

Normally, this would present the PM with the most gaping of open goals. (“If it wasn’t so funny, it would be tragic that our great wartime leader shares his name with your pathetic pipsqueak of a candidate!”) But again, he chooses instead to fold his tent, bringing his well-worn speech to a premature conclusion, before engaging in a bit of banter with one of the bobbies protecting him – which concludes with the PM wearing the policeman’s helmet, and waving his arms as if to direct traffic, for the benefit of the cameras.

To My Father’s surprise, Marcia – whose attention would usually be fully focused on the PM at this point in proceedings – materialises at his shoulder, and murmurs confidentially, “Good to see him so relaxed this close to polling day.”

There is, perhaps, a faintly imploring note in her voice, which seems to imply she would appreciate confirmation from My Father that the PM’s lack of stomach for the fight can somehow be viewed in a positive light.

“Very good,” he replies, automatically. Not gurning and waggling, as he certainly would if he were familiar with that convention.

***

13:15

My Father’s spirits are somewhat lifted by a successful meeting

“Well, I think that went about as well as it could have done, don’t you?” remarks the PM confidentially, to My Father.

They are enjoying post-meeting beer and sandwiches in the AEU Convenor’s office at the Metro Vickers factory in Trafford Park. (The beer is from a Watney’s Party Seven, the sandwiches are ham and pickle. There is no vegan option.) The room is crowded, with the PM’s entourage, at least a dozen Union officials, and a couple of secretaries to pass around the sandwiches. (Marcia is the only other woman present.) The windows are open for much needed ventilation, and the noise of the five-thousand-strong crowd outside, slowly dispersing, in no rush to get back to work, is impossible to ignore. They sound in elevated spirits, a few hundred at least singing the PM’s name, in the manner of the somewhat larger crowds that congregate on Saturday afternoons at the neighbouring football stadium.

“Sorry?” says My Father, failing to catch the PM’s words above the background noise.

“I said, I thought that went well?” the PM repeats, louder.

“Very well,” says My Father. And this time, he means what he says. This final major event of the campaign has been a triumph for the PM. He has made light of the tricky outdoor conditions (his speech has been delivered from the trailer of a lorry in the aerodrome-like car park of this gargantuan industrial complex). For the benefit of the press, who have been present in force, he has succinctly but savagely assaulted the Leader of the Opposition for his shamelessly self-interested devaluation scare (“anti-British and derogatory to sterling”). And he has not only held the crowd in the palm of his hand; he has, metaphorically speaking, affectionately tickled each and every one of them under the chin. He has even taken the minor risk of reminding this gathering of hard-bitten Mancunian working men that his allegiances lie on the wrong side of the Pennines (“like the greatest batsman in England, Geoffrey Boycott, I intend to go on and on!”), and they have laughed indulgently, and responded with a few affectionate cat-calls.

“Very, very well indeed, PM,” repeats My Father, more emphatically. And, as the PM smiles in acknowledgement, and raises his glass, My Father is struck by the transformation in his appearance. Suddenly, he looks 10 years younger than he did earlier this morning. His eyes seem clearer, his skin smoother and less sallow, his hair more lustrous. With the love of his people coursing through his veins, the PM glows and preens like a perfectly prepared racehorse parading around the paddock, before the off.

Surely he can’t lose tomorrow, My Father allows himself to think, for what will turn out to be one last time.

***

14:45

My Father is highly unlikely to taste My Mother’s latest cake

In the airy high-ceilinged kitchen of her substantial family home in the Surrey commuter-belt, My Mother is about to bake a cake. The French doors are open onto the airless garden, where the afternoon sun continues to scorch the parched lawn, but inside it’s comfortably cool; and, to add to the air of summery serenity, the Radio 4 afternoon play is burbling unthreateningly away to itself in the background. Although My Mother has made this cake many times before, she has her old dog-eared exercise-book of favourite recipes open on the table.

Pre-heat the oven to gas mark 5….

Watching her make her preparations – slamming down bags of flour and sugar on the melamine worktop, twisting the bowl of her Kenwood mixer into place with enough force to snap a bull mastiff’s neck – you might think she is angry. But nothing could be further from the truth. Angry? Whatever should she be angry about?

No, what My Mother feels is disappointment – and for multiple reasons. To begin with, she is disappointed because she knows, even before she has baked it, that no one will eat her cake. It’s one that, until quite recently, her children would have fallen upon like ravenous locusts; a rather ingenious variation, of her own devising, on the classic Victoria sponge, involving the addition of a generous portion of chopped stem ginger, and half a pint of Rose’s Lime Cordial. These days, though, none of them is remotely interested in cake, however delicious.

Thoroughly grease two 8-inch sandwich tins, and line with baking-paper.

My Father’s Elder Son, who has just finished his A levels, only emerges from his fetid bedroom when those of his friends who have passed their driving tests pull up outside the house in ancient Hillman Imps and Triumph Heralds, and raucously hoot their horns to summon him. And when he does stay home, he doesn’t trifle with snacks, preferring to sustain himself with gargantuan fry-ups, which he assembles with impressive speed and precision, cracking eggs on the edge of the pan one-handed. My Father’s Younger Son – a sombre unsociable boy, who leaves the house only to take part in various sporting activities – is much more often present, but even more narrowly focused gastronomically than his brother, his diet consisting almost exclusively of toast spread dangerously thick with Marmite. And My Father’s Daughter, not yet nine, is already incubating an eating disorder; unconsciously aware that, for her gender, food is a richer source of anxiety than of nutrition, and that eating it with any sign of appetite or enjoyment (even at her age) is frowned upon.

Cream together 1/2lb Stork and 1/2lb caster sugar, in lovely new Kenwood mixer!

As for My Father himself – well, it’s a long, long time since he touched any of My Mother’s cakes. And how very disappointed she feels when she remembers – as she does now – how, in the early years of their marriage, he seemed to be permanently hungry; invariably delighted to wolf down anything prepared by her, even her less successful culinary experiments.

My Mother is aware that the powerfully pervasive disappointment she feels now is not entirely cake-related. It’s also fed by a much deeper rooted and more unsettling sense that the role she has played within her family – so conscientiously, and for so many years – is no longer valued or appreciated by anyone. The beds beyond number she has made! The fevered brows she has soothed with dampened flannels! The meals she has cooked! The lifts to friends’ houses (many of them quite distant) she has provided! The (thrice) repeated pain and indignity of childbirth! None of this seems to count for anything, any more.

Of course, My Mother knows that teenagers are rarely to be relied upon for thanks, or even unspoken gratitude. And she supposes that her children are no worse than other people’s, in this respect. But it is…. disappointing to be treated so thoughtlessly by them, just the same.

Add four eggs, 1/2lb self-raising flour, 1 tsp baking powder and a teacup of Rose’s Lime Cordial to the creamed sugar….

My Mother’s most profound disappointment, though, is in My Father, for his gradual, now almost complete, withdrawal from family life. She is tempted to think of this as a betrayal, though she realises that might bring her perilously close to feeling a wholly redundant anger towards him. But, with the best will in the world, she can’t find a way of seeing his actions as anything other than a clear-cut case of breach of contract. This life they live now, the one that has come into being slowly, insidiously, over the last four or five years, is, most emphatically, not what she imagined she was signing up to, in those hilariously distant-seeming early days of their relationship.

Mix, at slow speed, until you have a smooth soft greenish (!) batter….

Of course, from the start, it was understood between them that she was happy to relinquish her career, in order to focus all her energies on her no less valuable role as home-maker and family-builder-in-chief. Meanwhile, it was equally well accepted by both of them that My Father – the exceptionally able young man, of limitless promise – would turn his extravagant talents to a career in business, rising steadily, winning regular promotions and pay-rises, acquiring executive perks such as an expense account and perhaps a corner office…. while, crucially, always leaving work in time to be home to put the children to bed. And for the first decade or so of their marriage, My Father proved able, with only the very occasional wobble or slip, to walk this tightrope.

As her Kenwood continues to throb purposefully, My Mother remembers, almost dreamily, how devoted a husband and father he was at this period; putting on a funny croaky voice to call the office, pretending to be sick, on days when she was under-the-weather and in need of looking after; shepherding the children to the park on Sunday mornings, to let her have a lie-in; never once missing a school parents’ evening.

Now…. that era has vanished utterly, as if erased from history. My Father has become a different man. Over these past few years, all his devotion has melted away like a dusting of late-April snow, as the demands of his professional life have increased remorselessly. His career has become an all-consuming monster, which can seemingly only be satisfied by his near-constant absence from the family home, and his total abstention from the performance of all marital and paternal duties. And even when My Father does deign to spend a few hours under the same roof as his wife and children, he is almost always absent in spirit; too busy, too important, too distracted, to be fully – or even partially – engaged in dull suburban domesticity.

When the mixture is ready, stir in a generous handful of chopped stem ginger….

And now this wretched election! My Mother can barely contain her disappointment when she thinks of My Father’s renewed immersion in politics. Of course, she can see why he was so pathetically excited on being summoned to Downing Street, around 18 months ago, to discuss press strategy. Any man (men are such children!) would be thrilled to be interrogated by the Prime Minister on his particular little area of expertise.

And of course, My Mother shares – no one more staunchly – My Father’s political beliefs. In fact, she would say that, since they first met, as fellow-members of the Labour Club at Oxford, it is she who has shown the more fervent, more unswerving commitment to international Socialism, as the one true path to the betterment of the working man. My Father, she remembers with grim disappointment, didn’t even vote in the last election, having arrived home late and worse for wear on polling day, following his monthly lunch with the ad agency.

Divide the mixture between the two tins, and smooth with a spatula or back of a spoon….

But this ridiculous, reckless decision he has made – without any consultation with her – to give up three weeks of precious family time, to act as an unpaid (unpaid!) adviser on a campaign that Labour were clearly going to win anyway, without any help from him…. well, why on earth would he do that, when he already has a successful career of exactly the kind they both decided would be best for him, and for their (as yet non-existent) family, around the time they were married? How could such a brilliant man behave so stupidly?

My Mother hasn’t registered a word of the radio play, but now, as the three o’clock news follows the pips, the headlines have her full attention: “On the final day of campaigning before tomorrow’s election, most opinion polls are still predicting a comfortable Labour victory, though there are some signs of a last-minute narrowing of the gap between the parties…. “

Really, thinks My Mother. Really? How awful it would be if defeat were still to be snatched from the jaws of victory. For him and also, of course, for the country. How hard it would hit him. She doesn’t know for sure, because he hasn’t confided in her, but she strongly suspects that, in the event of the predicted Labour victory, he is planning to use his role in the successful campaign as a springboard for reviving his long abandoned ambition to achieve high elected office. How desperately sad it would be for him if instead, his reputation in political circles were to be tarnished for ever by association with a horrible unexpected galumphing failure.

Bake for around 20 minutes, until (greenish!) golden….

As My Mother closes the oven door, she is surprised to hear the front doorbell ring. She very rarely has visitors at this time of day, and the Jehovah’s Witnesses have called quite recently. She hurries out of the kitchen, brushing flour from her skirt and briefly checking her appearance in the hall mirror. Through the frosted glass of the front door, she can make out a blurred female outline, though not one she recognises.

She opens the door. And no, it isn’t anyone she has ever met before. But the woman who is standing there, on the doorstep of My Mother’s home, seems to think they know each other. At least, she sees no necessity to introduce herself.

“We need to talk,” she says. “May I come in?”

***

15:30

My Father fears the PM may accept a rock bun – Manchester Ardwick (Labour, majority 8,023)

“More lapsang souchong, PM?” says Kaufman, who is wearing his candy-striped blazer again, over what looks like cricket attire.

“No, thank you, Gerald,” says the PM, from his deck-chair.

The PM and his party are taking tea in the large well-tended garden belonging to one of Kaufman’s more affluent supporters.

“In that case, a rock bun, perhaps?”

For a moment, My Father thinks the PM is going to accept this offer. It’s pleasantly cool where they are sitting, in the shade thrown across the lawn by a large willow tree. There is a low hubbub of conversation, from a small gaggle of local Labour supporters invited to meet the PM, and a slightly louder humming from the numerous bees at work in the flower-beds. The deckchairs are surprisingly comfortable.

But My Father’s fears are without foundation. The PM has started to haul himself effortfully to his feet. “Thank you again, Gerald. But, delightful as this part of your constituency is, and much as I would like to linger among your charming supporters, I have a timetable to which I must adhere. Or Marcia will be scolding me!”

Marcia and Kaufman both laugh at this.

“As if I would dare to scold you, PM,” says Marcia, glancing at her watch.

***

15:25

My Father’s Younger Son misses his chance to impress his classmates with the sophistication of his musical taste

As the guitar of Tony TS McPhee howls and whines its way towards a climax, while the Groundhogs’ mighty rhythm section thunders and booms beneath, like a pile-up between multiple HGVs laden with high explosive in an underground car park, a certain amount of tentative seated head-banging breaks out towards the back of the classroom, where Form 2 Alpha’s Music Appreciation session is in progress.

Eventually – though not before hopes have been raised and dashed by three or four false endings – the cacophony subsides into silence, and Mr Husband (who has a passion for Schubert’s Lieder) leaps forward to lift the stylus, before the next track can begin.

“Well, thank you very much indeed, Kirkland, for delighting us with that,” he says, unable to keep the disdain out of his voice. He hurries on, in the hope of forestalling retaliatory heckling. “Would anyone care to comment on their response to the piece?”

This provokes snorts of derisive laughter from the rear two rows of desks. Piece! The poncey little poof just called Rich Man, Poor Man by the Groundhogs a “piece”! He’ll be wittering on about tempo, and cadenzas, and harmonic modulation next.

Feigning unconcern, as he is forced to do dozens of times in every teaching day, Mr Husband raises his voice to make himself heard. “Well, in that case, let’s move on. Who else has a disc for us?

My Father’s Younger Son is acutely aware that there is only just time for the class to listen to After the Flood in its entirety (interrupting it would be unthinkable), and for him to say the “magnificent densely textured epic” thing, before the bell signalling the end of the school day. And four or five of his classmates still have unplayed albums on their desks in front of them, so he knows he urgently needs to attract Mr Husband’s attention if his is to be chosen. But now that the moment has arrived, a lassitude creeps over him. His arms, one of which he would need to raise immediately, lie heavy and lifeless before him. And somehow, he no longer feels any of his earlier certainty that demonstrating the superiority of his musical taste to his classmates will bring him any satisfaction, or serve to raise him in their esteem. Suddenly, everything – absolutely everything, even progressive rock – seems dark and unforgiving and futile to him.

And so Form 2 Alpha’s Musical Appreciation session concludes with two shorter pieces, by a quartet named Blodwyn Pig and the up-and-coming young American composer and instrumentalist John Denver.

***

16.55

My Father finally gets around to calling My Mother, but chooses an inopportune moment

In her airy high-ceilinged kitchen – which is now filled with acrid black smoke, only slowly dispersing through the open French doors – My Mother is trying very hard not to weep. She swallows once, twice, three times, but the constriction in her throat refuses to budge, as does the prickly heat behind her eyes.

Her cake is a charred ruin, retaining not even the faintest tinge of green. The two tins stand smouldering on the cooling rack. The oven continues to belch smoke. My Mother screws up her face tightly, as if to prevent moisture from seeping out. She feels that if she allows even a single tear to trickle down her cheek, there may be no end to the inundation.

The moment passes. She exhales heavily. She is not going to allow a mere baking mishap to defeat her. She will start again, and make the best Lime and Ginger Sponge she has ever made. True, nobody will eat it, which is disappointing. But she, My Mother, will – unlike certain other members of her family – have faithfully discharged her obligations. She will not be to blame if a situation should arise in which cake is urgently required, and there is no cake. She will have betrayed no one.

Donning oven-gloves, My Mother carefully picks up the super-heated remains of her first cake and, using a wooden spoon, shovels them down her new waste-disposal unit, which chugs and growls hungrily as it consumes them.

The air is clearing now. My Mother checks her ingredients, and finds that she has enough. (She is a little low on Stork, but she is fairly sure she has read somewhere that’s it possible to use butter instead, if absolutely necessary.) She flips the page in her old exercise-book, to return to the beginning of the recipe, and then sets to work with the scouring pad to return her elderly cake-tins (received as a wedding-present almost exactly 20 years ago) to serviceable condition.

A few minutes later, while she is creaming together the margarine, butter and sugar, she hears My Father’s Elder Son come in, and head straight upstairs to his room (she can instantly distinguish any member of her family by their footsteps on the stairs). It’s unusual for him to be home before My Father’s Younger Son. It almost certainly means that he will be going out again shortly with his friends, and has returned to change and wash his hair, before one of them calls by to pick him up. It’s possible he shouts a greeting as he passes the kitchen door, but if so, it’s lost in the whirr and thrum of her Kenwood.

A little later again, the phone rings. Uncharacteristically, My Mother ignores it. She tells herself this is perfectly sensible, since she has cake mixture on her hands, and, in any case, the call will very probably be for My Father’s Elder Son. But she’s well aware the real reason she doesn’t want to answer the phone is related to the sense of dread within her. It’s a feeling she has lived with for as long as she can remember, but recently it’s become much stronger, and more physically present in her life; as if she has a toxic gaseous bubble lodged in her abdomen, slowly but inexorably inflating, day by day. And today, since the doorbell rang an hour or so ago, it feels as if that bubble has ballooned in size, and become lethally unstable, to the point where it seems certain – very soon now – to explode, with devastating consequences. Surely, all it would take is one more incursion on her precariously maintained equilibrium….

The phone continues to ring. My Father’s Elder Son doesn’t answer, presumably because he is taking one of his epic 30-minute showers. And then it occurs to My Mother that it could be My Father’s Younger Son, who has cricket nets after school on Wednesday, and sometimes calls from the station for a lift, when he’s more than usually tired.

Humming casually, she snatches up the receiver.

“Hello?”

She hears only emptiness, and then a dialling tone. The caller must have hung up, momentarily before she answered. She resumes humming. Her main feeling is relief that she doesn’t have to speak to anyone; but, nothing if not conscientious, she is also aware that My Father’s Younger Son may, at this moment, be resigning himself to walking the three-quarters of a mile home from the station. (Wouldn’t it be useful, she thinks in passing, if there was some way of knowing who had called, in a situation like this?)

*

In his room at the Adelphi Hotel in Liverpool, where the PM’s party has just checked in, My Father is puzzled by his unanswered call. At this time of day, he would expect My Mother, and at least two of his children, to be at home. (My Father’s Daughter is, in fact, having tea with a friend.) His strongest feeling is relief that he doesn’t have to speak to My Mother, closely followed by frustration. He knows he must speak to her, imperatively, today. Not, of course, that he is planning to have The Conversation with her. That will have to wait until the weekend, he supposes (though this prospect seems unimaginably distant, there being the little matter of a general election, on which depend all My Father’s hopes and schemes for the remainder of his life, standing between now and then). But he needs, urgently, to lay the foundations for The Conversation. He needs – somehow, miraculously – to find words that will provide My Mother with a degree of reassurance that all is well between them, so that she will be as amenable and receptive as possible when he finally sets out his proposals for the next phase of their family life. The one in which he leaves his wife and children, but definitely doesn’t go to live with his mistress. At least, not straight away.

My Father sighs. He still has around half an hour of R&R, as Marcia calls it, before the evening’s campaigning begins. He will try calling home (he stumbles uncomfortably over the word as he thinks it) again before they leave for the PM’s Huyton constituency.

He picks up the phone, to call the Woman He Loves. But again, he is out of luck. In the basement kitchen of her high narrow home in North London, the phone rings unanswered. In this case, he is not particularly surprised. The boys are probably at their respective music lessons; Consuela doesn’t come on Wednesday; and the Woman He Loves must still be at her studio, where she does not permit modern telecommunications to impinge upon her creative process. He’ll call her again at bedtime.

*

A little later, as My Mother is spooning the new mixture into the clean tins, the phone rings. This time she doesn’t hesitate. My Father’s Elder Son is probably still in the shower. My Father’s Younger Son may need a lift. My Father’s Daughter may have broken her arm playing on her friend’s trampoline. Humming in a notably relaxed manner, she picks up the receiver.

“Hello?”

“It’s me. I’m really sorry I haven’t called – ”

“That’s all right,” she cuts him off in mid-apology.

“But the campaign has been completely – ”

“I’m afraid I can’t talk now. I have a cake in the oven.”

This is, strictly speaking, not true. But she is about to put the cake in the oven; and, surely, it’s entirely reasonable that she should want to avoid any possibility of being distracted, after what happened to the last one?

“OK, I’ll try to call again la- ”

“That’s perfectly all right,” she says, brightly, using her hand to cut the line more quickly than she can replace the receiver.

*

A little later, with all the smoke now cleared and a delicious gingery aroma wafting around My Mother’s high-ceilinged kitchen, she hears My Father’s Younger Son come in. He, too, disappears upstairs with no more than a grunt, possibly of greeting, as he passes the kitchen door.

“I’m making a cake!” calls out My Mother, gaily, after him. “Your favourite – ginger and lime! Ready soon!”

No reply. She remembers how My Father’s Younger Son used to love scraping the mixing bowl whenever she baked. She swallows hard, and screws up her face as tightly as she can. Not a single tear.

Now, how long has her cake been in the oven?

***

22:15

My Father still struggles to understand the appeal of association football

Not for the first time, My Father finds himself bewildered that so many serious and intelligent people can take such an obsessive interest in a group of men, much less well educated than themselves, chasing a ball around a rectangle of muddy grass. No sooner has the weary campaigning party straggled back into the presidential suite at the Adelphi than the PM has switched on the TV, so that he and his companions can enjoy a match between West Germany and Italy. This seems, as far as My Father understands, to be some kind of sequel to the contest his sons were watching on Sunday. He wonders briefly if, back at home – the word seems more jarringly discomforting every time he thinks of it – they are watching this one, too.

(They aren’t. My Father’s Elder Son is sitting cross-legged on the floor of the garden annexe belonging to a friend’s house, which serves as a rehearsal room for the band he’s in. A dense narcotic fug hangs over the circle of his countercultural contemporaries of which he forms part – most of whom, like him, will shortly be applying to Oxbridge. My Father’s Younger Son, who has school in the morning, is already in bed, where he is listening to John Peel on a transistor radio, and trying to persuade himself he is enjoying the drunken crooning of Kevin Ayers.)

The match is in its early stages, but Italy are already a goal up, which seems to please the PM. “Come on you Eyeties!” he exclaims when he sees the score. “We can’t let those Krauts get through to the final after beating our boys so luckily!”

My Father is appalled; not by the ethnically derogatory language, but by the fact the PM cares so much about this match, when it can have no possible bearing on tomorrow’s result. Whatever damage may or may not have been done to Labour’s prospects by England’s defeat, surely whether West Germany or Italy win today can make not the faintest difference at the polls?

And yet, My Father reflects, football does seem, inexplicably, to be much more effective than politics in arousing a passionate sense of allegiance, at least in this benighted part of the country. He thinks of the meeting they have just attended. The PM was warmly received by a fullish house at the Empire Theatre. After 20 years as a local MP, by far the most successful ever to represent the city, he has been awarded a kind of honorary Scouser status. And in his speech, the PM played, skilfully as ever, on the strength of this bond. He teased his audience repeatedly, including shamelessly recycling the Geoffrey Boycott gag, which had gone down well at lunchtime. He theatrically tossed aside his notes (which, in any case, he has barely referred to since the earliest days of the campaign), in order to address such old friends in a more intimate and unmediated manner. And he veered off into brisk and well informed analysis of local political issues (some crackpot scheme to pour public money into “regenerating” the docks for the benefit of middle-class incomers was given a brief but thorough drubbing).

All in all, it was an entirely successful performance. Yet the response of the crowd to the PM seemed cool, even frosty, compared to the bedlam that broke loose when he introduced two beefy young men, apparently representative of the city’s best known football clubs. They were wearing contrasting scarves – one red and white, the other blue and white – but otherwise, they seemed fairly interchangeable to My Father; tightly shirted, bulky of thigh, luxuriantly sideburned. To the crowd, though, they were antithetical gods, each adored and despised by approximately 50% of those present. For a few moments, as they stood alongside each other, waving sheepishly, unsure what else was expected of them, it seemed possible that a riot might be about to break out between the baying factions. But then the PM stepped forward and shook each of them by the hand, before pulling them together, and raising their hands above his head, like a boxing referee declaring a draw, at which the entire crowd howled and stamped and clapped in unified approval, for what seemed like quarter of an hour.

Of the several hundred people in the auditorium, only My Father – and of course Marcia – were focused on the PM, as this scene played out. So the chances are, My Father thinks, that no one else was conscious of the ineffable weariness emanating from him, the detectably valedictory note in the way he works the crowd; the sense of a master-politician, just past the very apex of his powers.

Now, a couple of hours later, the fatigue is almost overwhelming. On the TV, the match seems to have reached some kind of intermission, and men with impenetrable accents are discussing what has occurred so far, as well as what they expect to happen when play resumes. Slumped on the sofa alongside Mary, who is knitting, the PM is having difficulty keeping his eyes open, and repeatedly jerks his head upright, almost spilling the tumbler of Scotch that he is cradling to his stomach in his right hand.

“Well, it’s past my bedtime,” says Mary, in the forlorn hope that her husband may take this as his cue to retire. In 40 odd years of campaigning, the PM has never been the first member of his team to call it a day.

“We’ll just enjoy watching our German friends taste defeat,” he replies. “And then we’ll all get an early night, to be ready for what tomorrow brings!”

My Father’s spirits plunge to new depths. First, there’s the clearly implied command that all the PM’s team must see out the rest of this ghastly football match, when all My Father wants to do is get back to his room and call the Woman He Loves. And then, much more disturbingly, there’s that fatalistic “what tomorrow brings”. Twenty four hours from now, the first results will be coming in. And for the PM, My Father realises, they – and everything that follows from them – are in the lap of the gods.

*

“And now, to conclude our evening’s entertainment,” murmurs John Peel conspiratorially, in his finest faux-Liverpudlian, “I think we might treat ourselves to something epic from Van der Graaf Generator’s rather fine latest platter….”

Before the portentous opening Hammond organ chords of After the Flood can be joined by the parping sax and multi-layered acoustic guitars, My Father’s Younger Son has switched off his radio. He is tired. He wants the day to end. He is not even completely sure any more that he prefers progressive to blues-rock.

*

The football is almost over. It has, apparently, been a good match, and the PM has perked up considerably. As the final seconds tick away, with Italy still a goal to the good, he is sounding a lot more positive than he was earlier.

“Well, Marcia, gentlemen, a most satisfactory result. As I am sure we will also be saying tomorrow night!”

“Schnellinger!” screams the TV commentator, whom anyone but My Father would recognise as Kenneth Wolstenholme. “They thought it was all over…. but it isn’t now!”

This, for some reason, causes the PM to splutter, mirthlessly. West Germany have scored. Which, My Father assumes, means the match is a draw, and honours for this spectacularly dull and protracted contest will have to be shared. The football equivalent of a hung parliament, he supposes. Definitely not the desired result tomorrow, but better by far than the utter unmitigated catastrophe of defeat.

“So,” says the PM, rubbing his hands together, resigned but resolute. “Extra time!”

*

By chance, it is almost exactly at this same moment that the England team – bleary-eyed and, in many cases, extremely drunk after a 14-hour flight from Mexico City, via JFK – are pushing their baggage trolleys into Arrivals at Heathrow.

Behind the barrier, a meagre crowd awaits them; a couple of dozen die-hard fans, and a minimal press contingent. As the players appear, there is a ripple of applause, and a few consolatory shouts. A solitary hand-made banner reads, ‘PROUD OF YOU BETTER LUCK NEXT TIME”.

With the exception of Gordon Banks, who waves and smiles ruefully at the fans, the players shuffle by without making eye-contact. Considering this is a team that went into the World Cup as defending champions, and widely expected to retain the trophy, the mood remains surprisingly forgiving and free from rancour.

In fact, there is only one less-than-friendly voice, which makes itself heard – a sotto voce mutter – as Banks’s semi-final understudy somehow allows his BOAC hold-all to slip from his trolley, and fall to the floor.

“You useless wanker, Bonetti!”

*****