Sunday

17 June 1970

09:35

My Father and My Mother discuss the future of their marriage

“Tarry awhile, my lord. I would’st have speech with thee!”

Oh fuck, thinks My Father, not that! Since their earliest days together, when she was studying English Literature at Oxford, My Mother has made a habit of lapsing into mock-Shakespearean at times of heightened tension between them. It’s an affectation My Father has come to hate – and fear, too, because it invariably means she is about to say something that she is unable to utter in her own voice. Normally, in recent years, his response has been simply to ignore her; to give her absolutely no encouragement. But today, he is keenly aware that a deeply uncomfortable conversation – the most uncomfortable he will ever be party to – is exactly what he needs to initiate. So instead of taking his coffee (Maxwell House – so nasty and unsophisticated!) and escaping to his study, as he was planning to do, he sits down diagonally opposite her at the kitchen table, where she has been having breakfast, and says, through gritted teeth:

“Speak on, my lady.”

And so it begins, the conversation that will determine the course of their future lives. Each of them is prepared for it. In My Father’s case, he has been imagining, in detail, what they will both say when this moment comes, for many months; and for years before that, he has buffed and burnished phrases and whole sentences for use in a situation of exactly this kind. And, of course, he is a renowned wordsmith, acknowledged by his peers to be one of London’s most highly skilled purveyors of persuasive language. Yet, when it comes to dictating the course of this coming colloquy, My Father knows he is no match for My Mother.

Throughout her life, in any situation that can be foreseen, My Mother knows exactly what she intends to say. These days, for the vast majority of daily interactions, she no longer needs to give this conscious thought. She has in her head an extensive library of standard scripts ready for use, with a minimum of on-the-spot adaptation, at a moment’s notice.

When the milkman makes his monthly visit for payment, for example, she will always start with surprise at seeing him (“Good heavens, that time again already?”), before making a comment, personalised to him, about the weather (“I don’t envy your job on days like this!”), before glancing at the bill he gives her, and remarking positively on the excellent value that milk represents (“that’s really not a lot when you think how good it is for young bones!”), before enquiring, as she hands over the cash, about after his family (“and I hope the little one is thriving?”), before, as he gives her change, cutting the conversation short with one of three egalitarian-sounding excuses (“something boiling on the hob/kitchen floor half-cleaned/youngest in bed with a sniffle and in need of hot drink”).

And then there are less routine encounters – like the one she is about to have with My Father – which require a more bespoke approach, with meticulous and highly detailed pre-scripting. In either case, though, her goal is the same: to extinguish any possibility of spontaneity; to nullify any attempt on the part of her interlocutor to make a genuine human connection; to head off any twists or turns in the conversation that may threaten to take it towards an unexpected destination.

“I’m so sorry about…. that,” says My Mother, directing her gaze towards the Sunday papers, spread out carelessly on the table.

Bizarrely, they have fallen open in such a way that all the most apocalyptic post-election headlines are clearly displayed, forming a kind of montage. Words like CALAMITY, DISASTER and HUMBLED jostle with more thoughtful questions, such as WHAT WENT WRONG? and Where next for sorry Labour?

“You must be so desperately disappointed?” she continues, with warm concern.

Does My Mother feel the faintest qualm of conscience about weaponising the election defeat that she has, in a very small way, helped to bring about? Perhaps, in purely political terms, she does. Her allegiance to Labour is an important part of the person she has become, and can’t have been lightly cast aside. But what she felt in that polling booth on Thursday – an overwhelming need to wield her vote against My Father’s withdrawal from family life, against his ridiculous renewed political ambitions, against his betrayal of everything they have built together – was a hundred times more powerful than her loyalty to the People’s Party.

My Father hasn’t spoken yet, but already he feels control of the conversation starting to slip away from him. All he can do in response to My Mother’s opening thrust is try to depersonalise the disappointment a little.

“Well, of course, we were all hugely disappointed.”

“And it was so completely unexpected?”

My Father can only bring himself to grunt affirmatively at this.

“Everyone was so sure we were going to win,” My Mother goes on – her use of the first person plural shameless, in the circumstances.

My Father’s mind is racing now. How can he bridge from here to a calm and kind exposition of the reasons why he needs to leave his family? Even to a man of his exceptional abilities, it doesn’t seem possible.

“Not everyone,” he says. “In the last week so, there were definite signs. Particularly when they went for us on devaluation – “

“And the Tories were so hopeless, weren’t they? Everyone said so. Which must make it so much worse?”

And now, like a chess player foreseeing inevitable defeat half a dozen moves ahead, My Father understands exactly what My Mother is doing. She is administering a punishment beating with the Failure Stick. Partly, of course, in retribution for his past misdeeds. But, equally clearly, it’s also pre-emptive; a strong and unequivocal statement that from now on, he will be on a much shorter leash, as far as extra-curricular political activities – and anything else not strictly essential to his role as family breadwinner – are concerned. My Mother is bringing My Father to heel.

This is disastrous, My Father realises. Because if he is not going to tell My Mother about the Woman He Loves (and he definitely wants to postpone that revelation for as long as possible), how can he make a case for his relocation to London that isn’t based on the absolute necessity for him to pursue his career from a position close to the seat of power? And if he is now, officially, a useless defeated drudge, what career does he have to pursue? Why shouldn’t he spend the next 20 years commuting, brain-dead, to his dull job, from Worplesdon? My Father knows he must counter-attack, now.

“We were all hugely disappointed,” he repeats, in a more resolute tone. “But we’re pretty confident this government can’t last. We’d certainly be hoping for another election quite soon. Maybe within two years.”

There is some truth in this. Along with many pundits, My Father believes the new administration, with its fairly slender majority, will be short-lived. And it has occurred to him, too, that there will probably be a few safe Labour seats up for grabs very soon, as senior backbenchers, faced with a thankless spell in opposition, consider their career options. (The peerage route to high office, he realises, even in his more optimistic moments, is no longer open to him.)

“Really?” says My Mother, with enormous solicitude. “And if that should turn out to be the case, I suppose the Ex-PM would certainly want the same team running his campaign?” Again, as she speaks, her glance rakes the newspaper headlines.

My Father, as so often throughout their marriage, is left almost breathless by how vicious she can be. But he knows he can’t back down.

“Well, I think there’s actually a good chance he might. And hardly anyone is blaming the campaign for what happened on Thursday. But in any case, I’m not sure that’s the role I would want for myself, next time.”

Surely My Mother is now obliged to ask what role it is he envisages for himself? But no, she is giving My Father nothing. She just repeats “Next time” in a lightly amused and slightly quizzical tone that conveys pitying contempt for such self-delusive thinking, and picks up the Sunday Times, which is open on LABOUR’S DOOMSDAY!

So far, the conversation has gone almost exactly as My Mother expects. But now she makes her first mistake. She allows herself a moment to enjoy her success, and perhaps to plan her next move. (She knows exactly what she wants: firm assurances from My Father that his involvement in politics has been conclusively terminated by his humiliating failure on Thursday. But is he ready to give them, or does he need to be softened up a bit more first?) In any case, her brief pause allows My Father to wrench the agenda away from her, by means of a flagrant non-sequitur.

“Which leads me onto something I need to tell you. Something very difficult, I’m afraid…. “

And now, barely pausing for breath, to prevent My Mother interrupting, My Father delivers his own prepared script. Calmly and kindly, he explains to her that, after much reflection, he has decided that, for the time being at least, he needs to be London-based, for pressing career reasons. And that he recognises this will be very difficult for her, although she will surely acknowledge that their needs and wishes have, over a long period, become increasingly incompatible? And that, though it may sound paradoxical, he has reached the conclusion it would be unfair on her to continue as they are now, living separate lives under the same roof. And that, although it may be – no, will be – hard on their children, it goes without saying that he will continue to meet all his paternal, and financial, responsibilities. And that, in fact, he believes he may become a better father, when freed from the confines of a suburban lifestyle that no longer suits him. And that he is very sure that, however she may feel now, she will come to share his belief that this reorganisation of their lives will be of benefit to everyone. And that he intends to implement this difficult decision he has reached with immediate effect.

Connoisseur of dire prognostications and worst-case scenarios though she is, My Mother has not foreseen this. As she listens to him, all the breath leaves her body. She feels as if she has been kicked in the stomach, by a horse. Can her husband really be telling her that he is leaving her?

“But where will you live?” she asks, weakly.

“Well, I’ve asked Ian if he can put me up for a few nights. But of course I can’t camp out on his sofa for long, so I’ll probably look for a studio flat.”

Damn! He didn’t want to tell this lie. At least, not yet. But there was no avoiding it; and now, of course, My Mother is going to ask follow-up questions. Where will the studio flat be? How much will it cost? What will be the sleeping arrangements when the children visit him?

But before she can speak, the phone rings. And this time, it’s My Father who is eager to answer it. Sunday morning phone calls are nearly always from journalists. And he suspects this may be Aitken, in search of material for his Tuesday column, which will no doubt dissect the reasons for the PM’s defeat.

My Mother, for once in her life, barely responds to the phone. She is staring ahead of her, eyes unfocused, like someone who has just received a heavy blow to the head.

Taking advantage of this, My Father murmurs, “Do you mind?” and leans back in his chair to bring the phone within reach.

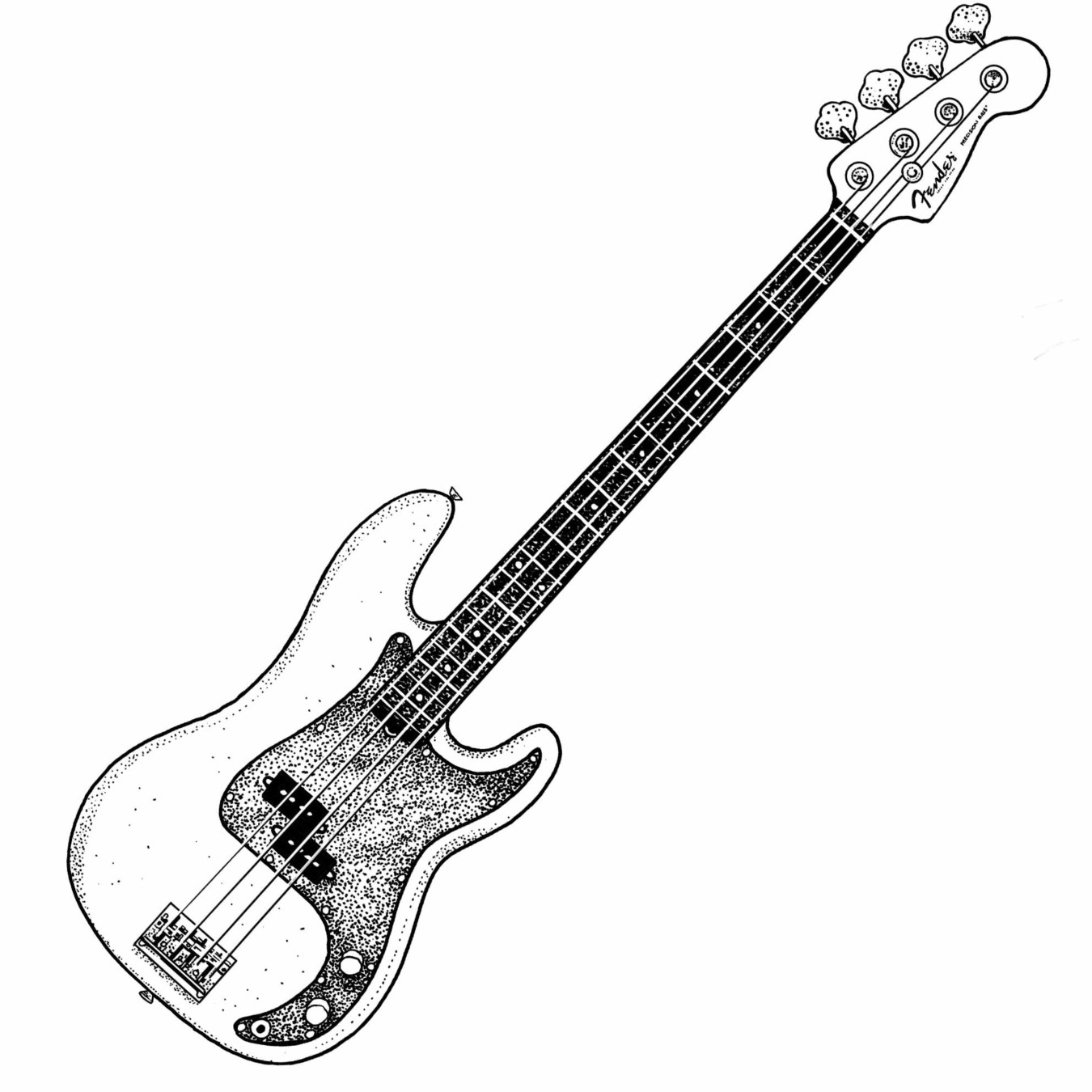

It isn’t Aitken. It’s My Father’s Elder Son, in need of a lift. Rather a long distance one. He is by a roundabout on the A303 just outside Andover. It’s a long story, but after last night’s gig, he and some friends decided to visit Stonehenge to celebrate the Summer solstice. And then one thing led to another. And anyway, now he is on his own, with his bass guitar, which is bloody heavy, and he has been trying to hitch for hours, but no one is stopping. And it’s miles to the nearest station, and anyway he doesn’t have any money, and he needs to get back in time to see Duster Bennett later, so he wonders if there’s any chance at all….

My Father goes. He feels he doesn’t have any choice. My Mother is in no fit state to drive. And, in any case, the timing of this emergency call – seconds after he has been piously declaring his determination not to shirk his paternal responsibilities – makes it imperative that he should go to the rescue.

*

His mission goes smoothly. The Sunday traffic is surprisingly light. And My Father and My Father’s Elder Son make their rendezvous without difficulty at a roadside Little Chef, where My Father’s Elder Son recovers from his ordeal by putting away a gargantuan Olympic Breakfast.

On the return journey, My Father’s Elder Son falls asleep in the passenger seat almost as soon as My Father starts the engine. My Father never knows what to say to his sons, so he is relieved there is no need to make conversation. Instead, as the boat-like Rover glides serenely homeward, through a sunlit Hampshire – and then Berkshire – afternoon, he has time to reflect on his earlier exchange with My Mother.

On the whole, he is satisfied with how it went. He has now done the dauntingly difficult thing he needed to do: he has made her aware that he is leaving her. True, he hasn’t been entirely transparent with her about his reasons for doing so, or about his new living arrangements. And of course she hasn’t had a chance to respond to what he has told her, because of the timing of My Father’s Elder Son’s cry for help. But he feels he has acquitted himself reasonably well. He has put his cards – well, most of them – on the table. And he has set in motion the process by which he will bring one chapter in his life to an end, and begin another happier, more successful one.

He wonders what My Mother’s next move will be.

*

When My Father eventually arrives back at the spacious family house in Worplesdon that is no longer his home, he finds My Mother restored to normal functioning. Which is to say that towards My Father’s Elder Son, she is jocular and brittle (“An impromptu trip to Stonehenge, how delightful! For everyone except your family!”); and towards My Father, cool and brisk. She has decided to treat his relocation scheme as an absurd whim, which it is probably wiser for others to indulge, until such time as he comes to his senses.

“Well, I’m sure you will be wanting to get back to your sofa-bed in Kilburn? Ian will be expecting you! I suppose you’ll be catching the 6.20?”

For a moment, My Father is completely wrong-footed. He has returned braced for a resumption of their earlier conversation, picking up at the point at which it was interrupted. Specifically, he has prepared himself for her rebuttal; a forensic demolition of his arguments in favour of their separation – starting with the obvious weakness of his claim that he currently has career goals that necessitate his urgent relocation to the capital. What career goals? What career? But, in his absence, she seems to have fast-forwarded through all the cut and thrust, jab and parry, that he has envisaged. And instead, here she is, offering him a chance to walk away, right now. But can he take her up on it? Does he owe her, his wife of very nearly 20 years, a more detailed explanation of the reasons for his desertion? And has he done enough to make the break with her – potentially, at least – definitive? If he leaves now, will he be able to look the Woman He Loves in the eye, and tell her it’s done?

The door of the cage stands open. If he hesitates for another moment, it may slam shut.

“Yes, that would be good,” he says, looking at his watch. “I think I’ve got time.”

“Don’t worry,” she says. “I’ll give you a lift.”

My Mother has decided to call My Father’s bluff.

“Daddy,” says My Father’s Daughter, who has appeared in the kitchen doorway while her parents have been talking.

He holds out his arms to her, and she runs into them, nestling her head against his stomach.

“Come on,” says My Mother, to My Father. And to My Father’s Daughter, “Your father has a train to catch. He has important work to do in London. On a Sunday evening.”

My Father strokes his daughter’s hair. How can he leave her?

“When will you be back?” she says.

What reply can he give her?

“Very soon,” he says softly, meaning you are my daughter and I love you and I intend to do my best to continue be the father you need me to be though at this moment I have absolutely no idea how that will work or when I will next see you.

“We’ll see,” says My Mother.

***

18:05

My Father is given a lift to the station by My Mother

It’s only 10 minutes’ walk to the station, so My Father has no real need of a lift. But My Mother has insisted. She feels she has responded skilfully to the shocking news of his intended desertion, and gained a decisive advantage by her tactic of supportive compliance. But there is still one subject she needs to raise with him. And now, as she applies all her strength and weight to coaxing the Rover’s ponderous tonnage out of Willow Drive and into Poplar Avenue, she addresses it as directly as she is able.

“By the by, sire – thy saucy whore hath honoured me with visitation, some days since!”

My Father’s blood turns to liquid nitrogen in his veins. His saucy whore? What the flaming fuck is she talking about? He has absolutely no idea. But he is instantly certain that nothing good can come from this line of conversation. He flails around for something non-self-incriminating to say.

But My Mother has planned this bit of dialogue down to the last comma, and the next line is hers.

“Your mistress! Your fancy woman! Your bit on the side!”

Sometimes My Mother gets stuck, linguistically, in the late 16th century. But on this occasion, having established the topic, she has returned immediately to the present day.

“She turned up on our doorstep just the other day, and invited herself in – as bold as brass!”

Until this point, her eyes have been fixed on the road ahead. But now she glances sideways to see how My Father reacts to this. He is too stunned, and horrified, to be aware that she is looking at him in a way that seems more amused than accusatory. His mighty brain is working at the limits of its capacity, trying to impose order on the information she has presented to him. Could the Woman He Loves really have done this? Surely not. But then again, she can sometimes be – and it’s the one of the things he loves about her – reckless, impulsive, volatile. So no, it’s definitely not impossible to imagine her feeling frustrated by his slow progress in escaping his marital ties, and deciding to take matters into her own hands. He can picture her slamming her way through the ancient Volvo’s gears en route for Worplesdon, hunched over the steering wheel, eyes blazing with righteous revelatory wrath. But if she did take it upon herself to end his marriage, why didn’t she warn him?

“And then she sat down in our sitting room, and told me all about your long relationship, and how you’d told her she was the only woman you’d ever really loved, and promised her – hundreds of time, she said – that you would leave your wife to be with her!”

How to respond to this? Panic-stricken, My Father is weighing up his options. Can he simply deny what the Woman He Loves has told My Mother? Or, if not, is there some mitigating plea he can enter? Perhaps he should “come clean” by admitting there was, in the past, some illicit relationship with this unexpected visitor to their home, now long over? But wait, My Father realises, surely the best thing to do would be to simply confess? My Mother will have to know about the Woman He Loves, and fairly soon. So why not acknowledge that his attempts to spare her feelings, at this stage of their separation, have failed, and bring things to a decisive conclusion right now? Suddenly, knowing this to be the correct option, My Father feels a surge of relief. The job he has dreaded has been done for him. All he needs to do is say to My Mother the words he now hears himself articulate:

“I’m so, so sorry I didn’t tell you sooner, but I thought it would be….”

But this sentence, wherever it’s heading, has no place in the conversation My Mother considers herself to be engaged in.

“Of course, I didn’t believe her,” she says. “Not for a second! Such a mousey little thing! Definitely not scarlet woman material!”

“No, really,” My Father protests. He can’t let this chance to make a clean break slip through his fingers. “I’m so sorry, but what she told you is completely – “

“But I thought I should tell you, because I wondered if you might want to report her to the police?”

“No, I’m trying to tell you, she’s – “

“Assuming you know who she is, of course? I thought perhaps a former colleague who had become unhealthily obsessed with a much older married man, which I know does happen?”

My Father folds. He knows from long experience that when My Mother has decided on a course of action, or an interpretation of events, there is no force, human or supernatural, capable of making her budge. My Mother believes she has received a visit from a madwoman, possibly with some tenuous historical connection to My Father. And nothing is going to change her position on that.

“Here we are,” she says brightly, as she pulls into the manicured forecourt of Worplesdon station. “And just in time.”

“Thanks,” says My Father, getting out of the car. And then he adds, “I’ll call you,” because he feels he has to say something.

“That reminds me,” says My Mother. “Does Ian still not have a phone?”

“No,” says My Father. “Still no phone.”

And so their marriage ends.

***

18:45

My Father resists temptation

On the train, My Father feels sick with shame and remorse. Last Sunday evening, when he made this same journey, everything in his immediate surroundings, and his entire world, seemed lambent with possibility. Everything he had ever wanted in life – love, happiness, success, recognition, wealth – was not just within his reach, but positively hurtling in his direction. Now, just seven days later, everything seems dull and tarnished. And it’s all because of him. Of course, he knows he isn’t personally to blame for Thursday. The PM might well have lost even more catastrophically without him. But, despite his exceptional powers, there was nothing he could do to avert disaster. And now his professional reputation stands in smoking ruins. As for how he has handled this…. transition in his personal life, My Father bows his head, and raises his hand to massage his luxuriant eyebrows. But nothing can soothe the sense of failure that grips him. He has lied to everyone who loves him, including his children. (When he left just now, he said nothing about the reasons for this departure.) And even when he has tried to tell the truth, he has failed, utterly.

What makes him feel saddest at this moment, though, is his sense that even the safe haven of his love for the Woman He Loves has been polluted. Yes, he finds her lack of restraint appealing, exciting even. But he’s shocked by what she has done – and, to be honest, quite pissed off with her. How could she possibly have justified to herself sending him off on the train to face My Mother, without telling him about her visit? What was she thinking? And now, how is he supposed to tell her that My Mother has simply refused to believe her story? And therefore that the most basic precondition for their becoming “real” – the ex-wife knowingly dumped – has not been met? He realises, of course, that this will not be possible, and that he will have to lie to the Woman in Loves. And lie in detail, too, because he knows she will interrogate him about exactly what transpired between him and My Mother; the precise terms on which they parted, and dissolved their partnership. The Woman My Father Loves is not one to be satisfied with airy reassurances.

Of course, My Father is desperate to spend the rest of his life with the Woman He Loves. But, at this instant, it strikes him, with sudden force, that what he really wants, right now, is to be with the Other Woman. He pictures her opening the door to him, as she did just seven days ago. She would be so happy – and surprised – to see him. And being with her, in her drab but really quite cosy flat, would be so uncomplicated! She would pour him a Scotch, from his special bottle, and run him a bath, with scented oils. And she would ask nothing of him. Nothing at all, beyond the pleasure of spending a few precious hours in his company. Perhaps he should call her when he gets to Waterloo, just to alert her to his imminent arrival – and allow her time to make herself look nice?

But, even as this thought is crossing his mind, My Father knows he is not going to call the Other Woman. Because it would be a bad thing to do. Morally wrong. Unkind. It’s less than a week since he brutally terminated their liaison, by post. He knows that only a terrible human being would reactivate her feelings towards him, just for the sake of one night of undemanding comfort, between nylon sheets. And My Father is not a terrible human being. Just a bad man. Which is to say, according to My Father’s world-view, a man.

*

When his train pulls into Waterloo a little later, My Father hurries along the platform and across the concourse, to the row of phone booths behind W H Smith. The call he makes is not to the Other Woman, or the Woman He Loves, but to a small hotel, just off Holborn, that has accommodated him on a number of occasions in the past on nights when he has missed the last train, or claimed to have done so. They have a room. He will stay there tonight. Starting his new life with the Woman He Loves – not yet entirely “real”, but becoming so – can wait until tomorrow.

*

In the Aztec Stadium, in Mexico City, just over 107,000 people suck in their breath as Pelé rises at the far post, and hangs suspended in mid-air for several seconds, just long enough for his forehead to meet the ball, crossed in from the left, with astonishing force, and direct it downwards past the flailing Italian goalkeeper.

In the butler’s sitting room at Chequers, the Ex-PM – who, like all football lovers, has switched his allegiance to Brazil following his own team’s elimination – punches the air.

In the playroom of the spacious family home in Worplesdon where My Father used to live, his sons react with similar enthusiasm. Neither of them will notice for several days that he has gone.

*****